Apartheid Wall Ruins Palestinians’ Lives

Source: Alalam.ir, 08-07-2008

West Bank--Palestinian farmers have stepped up protest against an ‘Israeli' "apartheid" wall that divided their farms and imposed a devastating effect on them.

The fertile fields of Jayyus stand out in the bone-dry landscape of the occupied West Bank but most farmers can't reach them, cut off from their own land by the Israeli separation barrier.

In a report on Jayyus released Monday in advance of the fourth anniversary of the ruling against the barrier by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at the Hague, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said that the barrier has had a devastating effect on the 3,500 people who live in that small agrarian community.

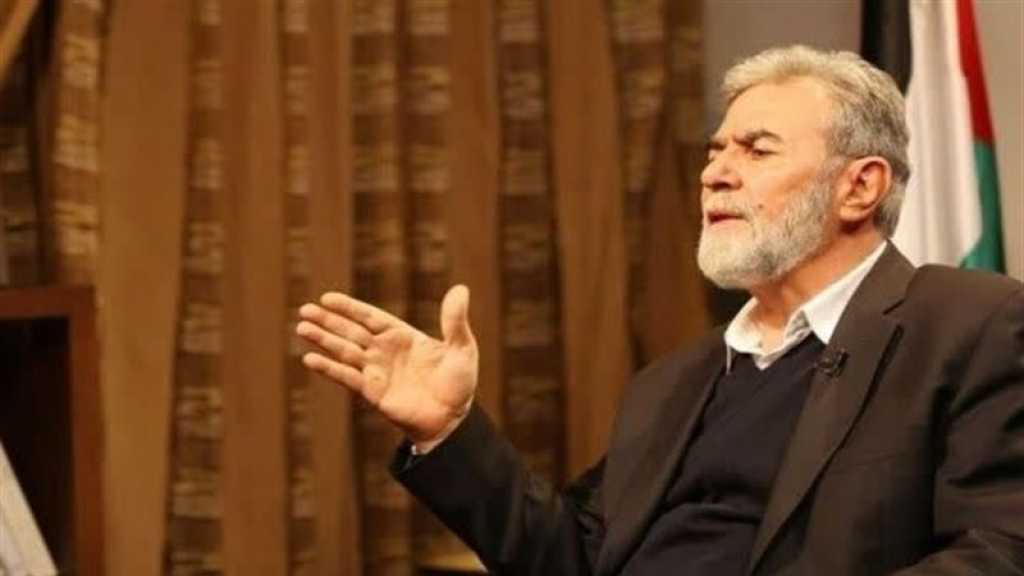

"The wall has transformed our life of happiness into desperation," said Jayyus mayor Mohammed Taher Jaber.

ICJ non-binding ruling calls for parts of the barrier built inside the West Bank to be torn down.

Farmers want the international community to press ‘Israeli' regime to follow the ICJ's decision made on July 9, 2004.

Perched on a hilltop in the northern West Bank, the town of 3,500 people is surrounded on three sides by a fence that forms part of the massive barrier the occupying regime is building around and mostly in the West Bank.

‘Israeli' regime authorities claim the barrier is needed to stop potential attackers from infiltrating into the Jewish settlements, but Palestinians denounce it as an "apartheid" wall aimed at grabbing their land and undermining the viability of their promised state.

To get to their own land, Jayyus farmers need to apply for "visitors' permits."

Jayyus residents and the OCHA say fewer than 20 percent of those who used to work on the land have been granted permits.

Far from dismantling the barrier, the Zionist regime has pressed ahead with its construction and completed about 200 km (125 miles) since the ICJ issued its order.

To date, ‘Israel' has completed construction of 57 percent of the projected 723 km (452 miles) of steel and concrete walls, fences and barbed wire, according to OCHA.

UN figures show that when completed, 87 percent of the barrier will be built on West Bank territory, which ‘Israel' occupied in 1967.

In Jayyus, the electronic fence completed in August 2003 stands right at the town, six km (3.75 miles) from the "Green Line," the armistice line drawn up after Israel's 1948 war with Arab armies and now considered the West Bank's boundary.

The barrier cuts off villagers from 860 hectares (2,125 acres) of their cultivated land, including 50,000 fruit and olive trees, 70 greenhouses and six groundwater wells.

To get to their lands, Jayyus farmers who have the required permits are only allowed to cross through designated gates at certain hours of the day.

"Why do they refuse to give us permits? So that the land gets neglected, and they can claim it after three years under absentee law," charges Shareef Khaleed, 65.

'Israelis' in the nearby Zufin settlement have their eyes on some of their fields as part of expansion projects for their community, according to OCHA.

Sweating profusely under the scorching sun, Khaleed points to empty fields alongside lush orchards and greenhouses.

Like many fellow farmers here, he is unable to work all his fields, as none of his sons or brothers could get the necessary permits.

Only those with a proven "connection to the land," which excludes tenant farmers, landless laborers and second-degree relatives of the land's owner can get permits, though this is not a guarantee.

To make matters worse for the farmers, the gates' limited opening hours force them to work in the heat of the day in summer and line up in the cold in winter.

If an accident happens in the field, the casualty has to wait until the scheduled opening time to seek treatment, sometimes more than four hours.

Only three trucks in Jayyus have permits to cross into the closed area.

The land is fertile and locals pride themselves on their crops of tomatoes, cucumbers, sweet peppers, eggplants, peaches, almonds and cabbage.

But because of the wall, buyers no longer travel to Jayyus, and farmers say they are now forced to sell their produce at a nearby market where competition has slashed prices dramatically.

Before the barrier was built, Jayyus farmers would produce about 9,000 tons of produce a year, now the figure is about half that, says Abdul-Latif Khalid, a hydrologist and a Jayyus farmer.

Many farmers have given up their fields or switched to lower-maintenance crops.

"Jayyus has transformed from a net exporter of food to a community where social hardship cases receive food aid," OCHA said in a recent document, adding that unemployment now stands at 70 percent.

"We are not talking of a land without people, we are talking of a fertile land and people who depend on it."

West Bank--Palestinian farmers have stepped up protest against an ‘Israeli' "apartheid" wall that divided their farms and imposed a devastating effect on them.

The fertile fields of Jayyus stand out in the bone-dry landscape of the occupied West Bank but most farmers can't reach them, cut off from their own land by the Israeli separation barrier.

In a report on Jayyus released Monday in advance of the fourth anniversary of the ruling against the barrier by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at the Hague, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said that the barrier has had a devastating effect on the 3,500 people who live in that small agrarian community.

"The wall has transformed our life of happiness into desperation," said Jayyus mayor Mohammed Taher Jaber.

ICJ non-binding ruling calls for parts of the barrier built inside the West Bank to be torn down.

Farmers want the international community to press ‘Israeli' regime to follow the ICJ's decision made on July 9, 2004.

Perched on a hilltop in the northern West Bank, the town of 3,500 people is surrounded on three sides by a fence that forms part of the massive barrier the occupying regime is building around and mostly in the West Bank.

‘Israeli' regime authorities claim the barrier is needed to stop potential attackers from infiltrating into the Jewish settlements, but Palestinians denounce it as an "apartheid" wall aimed at grabbing their land and undermining the viability of their promised state.

To get to their own land, Jayyus farmers need to apply for "visitors' permits."

Jayyus residents and the OCHA say fewer than 20 percent of those who used to work on the land have been granted permits.

Far from dismantling the barrier, the Zionist regime has pressed ahead with its construction and completed about 200 km (125 miles) since the ICJ issued its order.

To date, ‘Israel' has completed construction of 57 percent of the projected 723 km (452 miles) of steel and concrete walls, fences and barbed wire, according to OCHA.

UN figures show that when completed, 87 percent of the barrier will be built on West Bank territory, which ‘Israel' occupied in 1967.

In Jayyus, the electronic fence completed in August 2003 stands right at the town, six km (3.75 miles) from the "Green Line," the armistice line drawn up after Israel's 1948 war with Arab armies and now considered the West Bank's boundary.

The barrier cuts off villagers from 860 hectares (2,125 acres) of their cultivated land, including 50,000 fruit and olive trees, 70 greenhouses and six groundwater wells.

To get to their lands, Jayyus farmers who have the required permits are only allowed to cross through designated gates at certain hours of the day.

"Why do they refuse to give us permits? So that the land gets neglected, and they can claim it after three years under absentee law," charges Shareef Khaleed, 65.

'Israelis' in the nearby Zufin settlement have their eyes on some of their fields as part of expansion projects for their community, according to OCHA.

Sweating profusely under the scorching sun, Khaleed points to empty fields alongside lush orchards and greenhouses.

Like many fellow farmers here, he is unable to work all his fields, as none of his sons or brothers could get the necessary permits.

Only those with a proven "connection to the land," which excludes tenant farmers, landless laborers and second-degree relatives of the land's owner can get permits, though this is not a guarantee.

To make matters worse for the farmers, the gates' limited opening hours force them to work in the heat of the day in summer and line up in the cold in winter.

If an accident happens in the field, the casualty has to wait until the scheduled opening time to seek treatment, sometimes more than four hours.

Only three trucks in Jayyus have permits to cross into the closed area.

The land is fertile and locals pride themselves on their crops of tomatoes, cucumbers, sweet peppers, eggplants, peaches, almonds and cabbage.

But because of the wall, buyers no longer travel to Jayyus, and farmers say they are now forced to sell their produce at a nearby market where competition has slashed prices dramatically.

Before the barrier was built, Jayyus farmers would produce about 9,000 tons of produce a year, now the figure is about half that, says Abdul-Latif Khalid, a hydrologist and a Jayyus farmer.

Many farmers have given up their fields or switched to lower-maintenance crops.

"Jayyus has transformed from a net exporter of food to a community where social hardship cases receive food aid," OCHA said in a recent document, adding that unemployment now stands at 70 percent.

"We are not talking of a land without people, we are talking of a fertile land and people who depend on it."