Mines still stand out as scourge of South...Awareness campaigners still have work to do with locals, returnees, and visi

Source: Manar TV, 9-9-2000

Summary: The rules for avoiding land-mine accidents are not all that complicated, but raising land-mine awareness in the former occupation zone has proved a difficult task for activists.

Between 50,000 and 150,000 land mines are believed to lie buried in the South, planted by "Israel" from the early 1980s until the end of the occupation. Community-based organizations working for mine awareness have intensified their efforts in the South following the liberation in May. But the mines have still taken lives.

According to statistics from the Internal Security Forces, since liberation nine people have been killed and 63 wounded by mines in the South.

This wave of accidents has prompted a number of humanitarian organizations and the army to take mine-awareness campaigning more seriously.

Balamand University's Land Mine Research Center organizes many awareness activities, including lectures, training sessions and leaflet distribution.

The center targets three groups, said Habouba Aoun, who heads the center: locals, residents who returned after liberation, and visitors.

But four months after the liberation, awareness campaigns are not yet totally effective.

In Aoun's experience, since permanent residents are more attached to the soil and claim to know its perils well, they are more resistant to change. Newcomers, meanwhile, tend to underestimate the extent of land-mine presence in the seemingly virgin fields, putting them at risk as well.

"To most people awareness is only talk, and people always think, ‘it won't happen to me,'" said Aoun. As a result, campaigners use the slogan "You're better safe than sorry."

Some of the existing land-mine warnings are, "Keep out of mined areas where signs are up" and "If you find something unusual, don't touch it!"

But when locals are told to avoid using land that is suspected of being mine-infested, "shepherds and farmers demand an alternative," Aoun said.

For example, nothing stops shepherd Omar Mahmoud al-Ali from herding his 150 goats on an arid hill beside the former "Israeli" artillery position of Shrayky.

"I take care because I know the area very well," Ali said at his home in Dibbine. But he fears for his 16-year old sister, Intisar, who sometimes takes the herd out by herself, unaware of where danger lies.

Ali was surprised by a few near-disasters himself. He usually steers clear of the barbed-wire fence on the hill, where he suspects there are mines. Two months ago, Ali was about 10 meters from the fence and found himself surrounded by mines, clearly visible on the ground.

"I got away by stepping lightly on some rocks on the way back," he said. But one of Ali's goats wasn't as lucky as he was and stepped on a mine while it was grazing near the fence six months ago, shortly before the liberation.

"Nothing was left of the goat," he recalled.

Ali tells his stories with alarming ease, suggesting he rejects the possibility of becoming a land-mine victim.

Ali, who is in his 30s, said that as a boy, he amused himself by heating unexploded artillery shells with matches, placing them in old car tires and watching them explode as they rolled down the hillside.

Asked why he was not afraid, he said: "I have to live. I like herding goats. It's better than being around people."

Ali nodded at the bare patches on otherwise grassy terrain as a sign of the possible presence of mines. This is only one of the many telling signs recognized by experts. The shepherd did not know that mounds of earth, electric cables on the ground, protruding metal or piles of stone are also best avoided.

He recounted that in the past, UN peacekeepers used to paint rocks blue to mark the suspected presence of mines, signs he has come across several times.

Having lived in Beirut during the "Israeli" occupation, Hussein Deeb Qadbay was excited to return to his home in the once-occupied part of Kfar Tibnit.

But situated on the foot of a hill leading up to the abandoned "Israeli" artillery position of Ali Taher, his house is not far from a belt of mines believed to skirt the position and notorious for causing earlier accidents.

This, however, does not seem to worry Qadbay. To put his mind at ease, "I took a motorbike ride on the hill to make sure there weren't any mines. I didn't find any."

A common fallacy among residents is that land mines which are effective because they are concealed can be seen.

Asked about the possibility of stumbling across a mine by mistake, Qadbay replied: "Nothing would've happened to me because I was on a motorbike." Fallacy No. 2: where land mines are concerned, a motorbike is indestructible.

"I know nothing about land mines," admitted Qadbay's 9-year-old nephew, Assem Hayek, "except that there are some on up on the hill." Forbidden from straying too far from the house, Assem and his young relatives play in the small yard under their parents' supervision.

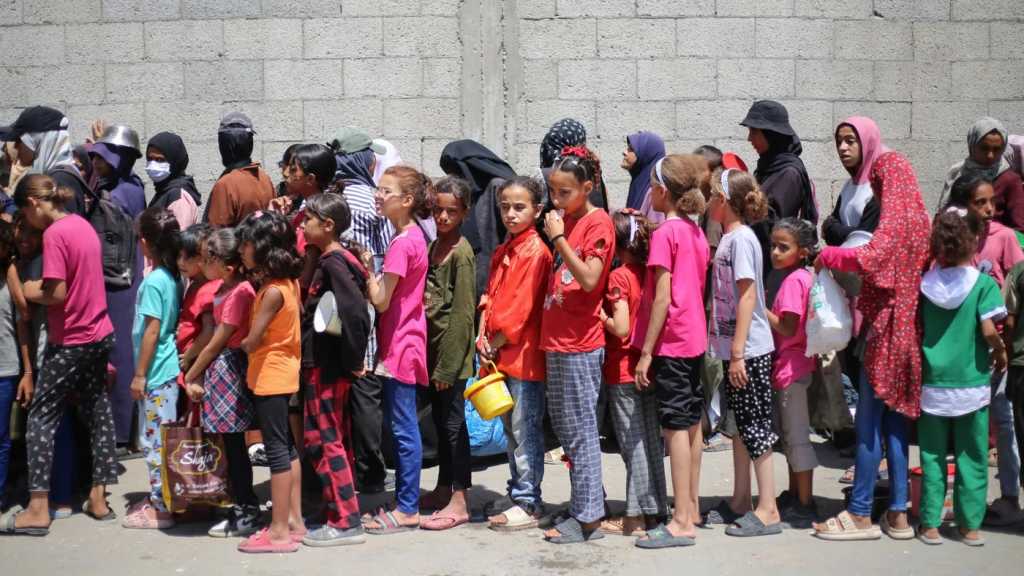

With their sense of curiosity, Children are most vulnerable to mine accidents. This is why the Land Mine Research Center, Save the Children and the army's National Demining Office target children in many of their awareness campaigns. They held a series of summer camps and workshops to give children the basic guidelines.

The center's efforts paid off: after attending a workshop in mid-August, 20 young volunteers founded the country's first land-mine awareness club, resolving to publicize the hazards of land mines and warn people, especially children, about suspected danger zones.

From their base at the Center for the Care of the Handicapped in Nabatieh, the volunteers are preparing awareness material and plan to hold lectures in their respective villages. According to Ghassan Rammal, who heads the center, "we've noticed awareness levels increased considerably since we began."

Prior to their workshop, volunteers used to go on outings in areas they would not dream of setting foot in today. The warning has apparently sunk in after just a five-day crash course.

"In the past, I sometimes used to go on field trips near my house, wander off the main roads or venture onto small paths, something I'd never do now," said volunteer Hussein Traboulsi from Deir al-Zahrani. "I might also have picked some strange-looking thing off the ground, not knowing it might explode."

Before attending the workshop, Faizeh Ismail's source of information about land mines was television, which according to her was "very limited."

The workshop acquainted her with areas suspected of having land mines, and one of them turned out to be a river where she and her family often visited.

"Now we don't go there at all," she said. "But now the club has to work to make sure no one else goes there until it's cleared of mines."