Georges Ibrahim Abdallah: The Prisoner Who Remained Free

By Mohamad Hammoud

Lebanon – Georges Ibrahim Abdallah was born in 1951 in Qoubayat, a stone-roofed Christian town nestled in Lebanon's northern mountains. By the time he was a teenager, “Israel” tanks had already begun crossing into South Lebanon; by his twenties, invasions had become routine. The 1978 onslaught left him physically wounded—shrapnel lodged in his thigh—but the moral wound was deeper. Watching Palestinian refugee camps bombed from land, sea, and air, he concluded that op-eds and petitions would never unseat an occupation backed by American steel and Zionist ideology. Liberation, he came to believe, must come at a cost.

In 1979, Georges Abdallah co-founded the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Factions [LARF], committed to confronting imperialism at its source. In the early eighties, he launched operations on French soil, targeting symbols of US and “Israel” power—including the assassinations of a military attaché and a diplomat. Arrested in Lyon in 1984 and sentenced to life in 1987, his real crime was not the act, but the idea: that resistance to occupation is a right, not terrorism.

From his first day inside France's Lannemezan Prison, Abdallah chose dignity over submission. He taped a photo of Che Guevara above his metal desk, began teaching himself Greek to read Gramsci in the original, and raised the Palestinian flag from his cell window every Nakba Day. While the world outside shifted—empires fell, Oslo collapsed, and the internet rose—the French parole board stamped "NON" year after year. Abdallah became eligible for release in 1999. A court granted parole in 2003, but the French government, under heavy pressure from Washington and Tel Aviv, refused to sign the deportation order. In 2013, Hillary Clinton personally urged France to “find a way to contest the legality” of his release. The cell door slammed shut once again.

Yet, despite spending 41 years behind bars, Georges Abdallah has never asked for a pardon. “I do not regret,” he told AFP in 2024. “I did what I had to do for Palestine and Lebanon”. He fasted in solidarity with hunger strikers, taught Arabic to other inmates, and wrote revolutionary communiqués that inspired a generation. Prison manuals describe the stages of inmate adjustment: shock, denial, acceptance. But Abdallah invented a fourth, resistance.

Though behind bars, Georges Abdallah is freer than most leaders in the Arab world. He refused to submit to imperialists and occupiers, even as some Arab rulers have imprisoned themselves in palaces built on humiliation. They are chained—not by iron bars, but by dependence and obedience to Washington and Tel Aviv. Abdallah could have walked out of prison long ago had he agreed to denounce the resistance or apologize for his past. But he chose to remain in his cell rather than kneel in a hall of power. He preferred life behind bars over a life of comfort bought with surrender. While some wear suits and sit on thrones, they are slaves in spirit. Abdallah, in a cell, remains free.

I know this story deeply because I, too, have walked through the fire. I was arrested in 2000 in the United States, accused of supporting Hezbollah and running a so-called “sleeper cell”. The judge sentenced me to 155 years—as if numbers could erase a life. I refused to betray my beliefs or the cause of resistance, no matter the price. I watched others cut deals, denounce their comrades or break under despair. I stood firm. The sentence was later reduced to thirty years, and after twenty-three years behind bars, I was granted compassionate release. The gates opened, but Palestine remained occupied. My body walked free, but my heart is still where they suffer.

People often ask how one survives without surrendering. The answer is not mystical—it is moral. You learn to stop measuring time by clocks and calendars. You measure it by how many mornings you rise without bowing. Abdallah taught that freedom is not a legal status; it is a state of being. It is the unbroken decision to stand with the oppressed, even when it costs you everything.

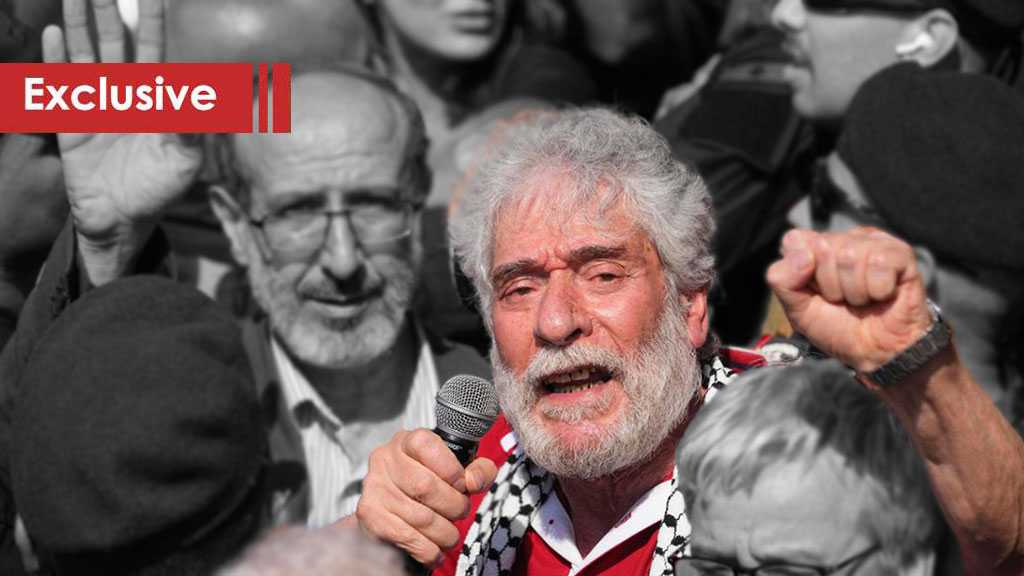

On July 25, 2025, six black vans left Lannemezan at 3:40 a.m., carrying Georges toward Toulouse-Blagnac Airport. In Beirut, the tarmac waited for him, covered in flags—Palestinian keys, Lebanese cedars, red stars and sickles. Abdallah stepped off the plane wearing a red shirt and keffiyeh, the same colors he had worn in his mugshot four decades earlier. “The martyrs are the compass,” he told the crowd. “We are only the travelers”. Classic Georges: modest, militant, unrepentant.

Tonight, I walk free streets, but I still carry the arithmetic of captivity—155, then 30, now zero. Yet the real number is one: one truth, one cause, one conscience. The occupiers measure victory in stolen land and years sentenced. The resistance measures it in convictions kept. I feel Georges' pain as my own because it is the pain shared by every dispossessed soul who understands that land can be taken—but conscience cannot.

We were never just inmates. We were witnesses. And Georges Abdallah remains a beacon—not only of what it means to resist but of what it means to stay human in the face of dehumanization. He reminds us that freedom does not begin when the bars are removed, but when the soul refuses to kneel. Until every last cell becomes a museum of cruelty, and every prisoner walks free, the resistance will not rest—and neither will we.